Why Medication Errors Happen When You Leave the Hospital

Leaving the hospital after a stay can feel like a victory - you’re finally going home. But for many older adults, that first week out is actually the most dangerous time for their health. About 1 in 5 seniors experience a medication error within three weeks of being discharged. These aren’t small mistakes. They’re wrong doses, missed pills, conflicting drugs, or medicines that weren’t even supposed to be taken anymore. And they often lead to another hospital trip - which is exactly what everyone wants to avoid.

The problem isn’t that doctors or nurses are careless. It’s that the system is broken. Hospitals give you a stack of new prescriptions, change old ones, and sometimes forget to tell your primary doctor or pharmacist what’s been adjusted. You leave with a list that doesn’t match what you were taking before. You’re tired, confused, and maybe still on pain meds. No wonder mistakes happen.

The One Step That Stops 67% of Errors

There’s one single action that cuts medication errors in half - and it’s not expensive, high-tech, or complicated. It’s medication reconciliation.

This isn’t just a form you sign. It’s a process where your medications are compared across three points: what you were taking before you came in, what you got in the hospital, and what you’re leaving with. A 2018 study in JAMA Internal Medicine showed that when pharmacists do this properly, medication discrepancies drop by 67%.

Here’s how it should work:

- On admission: A pharmacist or nurse collects your full list - including vitamins, herbal supplements, patches, and over-the-counter painkillers.

- During your stay: Any changes are documented and reviewed daily.

- At discharge: You get a clear, written list of every medicine you’re supposed to take, with dosages, times, and why you’re taking each one.

Too often, hospitals skip the first step. They assume they know what you’re on. They don’t check your brown bag. They don’t call your pharmacy. That’s where things go wrong.

Who Should Be Doing This - And Why It’s Not the Nurse

You might think the nurse handles your discharge meds. But nurses are stretched thin. They’re managing IVs, wound care, and family questions. Medication reconciliation is a job for a pharmacist.

Pharmacists are trained to spot dangerous interactions. They know that mixing warfarin with certain antibiotics can cause dangerous bleeding. They know that stopping an old blood pressure pill too fast can make your heart race. They know which over-the-counter cold meds are unsafe with heart conditions.

Studies show hospitals with pharmacist-led discharge teams reduce readmissions by 22-30%. In contrast, nurse-led programs without pharmacist input only cut errors by 10-15%. If your hospital doesn’t have a pharmacist at discharge, ask for one. It’s not a luxury - it’s the standard of care for seniors with five or more medications.

The Teach-Back Method: Don’t Just Get a List - Prove You Understand It

Getting a paper list isn’t enough. Many seniors don’t know what their meds are for. They might think “Lisinopril” is for headaches. Or they don’t realize they’re supposed to take insulin before meals, not after.

The Teach-Back method fixes this. It’s simple: after the pharmacist explains your meds, they ask you to explain them back in your own words. Not just “yes, I understand.” Actually say it out loud.

“So, I take this blue pill every morning with breakfast for my blood pressure, and this white pill at night for my heart rhythm. I stop the old one I was taking at home - that was the red one, right?”

If you can’t say it clearly, they keep explaining. A 2012 study found this boosted medication adherence by 32%. It’s not about being smart - it’s about being sure. And it’s especially critical for people with memory issues or limited health literacy.

What to Bring Home - And What to Throw Away

Before you leave the hospital, do this:

- Ask for a printed copy of your updated medication list - not just a digital one.

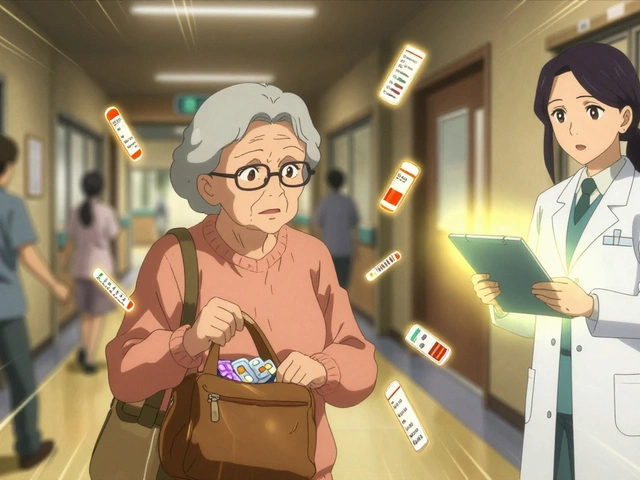

- Bring your brown bag - all your current pills, vitamins, creams, inhalers, and patches - to your discharge meeting. Let the pharmacist see exactly what you’ve been taking.

- Confirm which medicines you should stop. Many seniors are still taking drugs they were told to quit weeks ago.

- Ask: “Is this new medicine replacing an old one? Or is it in addition?”

Don’t assume the pharmacy will sort it out. Pharmacists at retail stores often don’t have access to your hospital records. They might fill a new prescription without knowing you’re no longer supposed to take the old one. That’s how double dosing happens.

Follow-Up Isn’t Optional - It’s Life-Saving

Waiting two weeks for your next doctor’s appointment is too long. For high-risk seniors - those with heart failure, COPD, kidney disease, or five or more meds - you need a check-in within seven days.

Here’s what that visit should include:

- Verification that you’re taking the right pills at the right times.

- Checking blood pressure, blood sugar, or INR levels if you’re on warfarin or insulin.

- Reviewing any side effects - dizziness, confusion, swelling, or nausea.

- Confirming you have the right supplies: syringes, test strips, pill organizers.

Telehealth visits work. Home health nurse visits work. Even a phone call from your pharmacy can help. But don’t wait. The first week out is when most errors happen.

Technology Can Help - But It’s Not a Magic Fix

Some hospitals use apps that send daily reminders with photos of your pills. Others have digital pill dispensers that unlock only when it’s time to take a dose. A 2023 study found these tools reduced errors by 41% in seniors with memory problems.

But don’t rely on tech alone. If you’re not comfortable with smartphones, don’t force it. A printed schedule taped to the fridge, with a family member checking in daily, can be just as effective.

The real value of technology is in communication between providers. If your hospital’s electronic record can talk to your doctor’s system, it cuts down on lost information. But only 35% of U.S. hospitals can do that reliably. So don’t assume it’s working. Always confirm.

What to Do If Your Hospital Doesn’t Do This Right

Not all hospitals have good transition programs. Rural hospitals, in particular, often lack pharmacists or follow-up systems. If you’re being discharged and no one’s talking about your meds properly, here’s what to do:

- Ask directly: “Will a pharmacist review my medications before I leave?”

- Request a written discharge summary with your full medication list.

- Ask for a referral to a home health nurse or community pharmacist who can do a follow-up visit.

- If you’re on Medicare, ask about Transition Care Management (TCM) services - they’re covered and paid for by Medicare if your hospital offers them.

- If you’re still confused after leaving, call your primary care doctor’s office and say: “I just got out of the hospital. I need help understanding my new meds.”

You have the right to safe care. You’re not being difficult - you’re being smart.

Real-Life Example: What Went Right

Mrs. Jenkins, 78, was discharged after a heart failure episode. She was on eight medications. At discharge, a pharmacist sat with her for 25 minutes. They used her brown bag to compare what she was taking at home versus what she got in the hospital. They found three old pills she was still taking - one of them was a blood thinner that conflicted with her new one.

The pharmacist used Teach-Back: “Mrs. Jenkins, tell me when you take your furosemide.” She said, “After lunch.” The pharmacist corrected her - it was supposed to be in the morning to avoid nighttime bathroom trips.

Three days later, a home health nurse visited. They checked her weight, blood pressure, and asked if she was having dizziness. No problems. No readmission. She’s been stable for six months.

That’s what safe transition looks like.

Nikhil Pattni

December 10 2025Look, I’ve been a pharmacist in Delhi for 22 years and let me tell you - this whole ‘medication reconciliation’ thing? It’s not rocket science but hospitals act like it is. In India, we don’t have fancy apps or digital records, but we do have brown bags. Every single patient brings their entire medicine cabinet - pills in ziplock bags, ointments in yogurt containers, even that one bottle labeled ‘for pain’ that no one remembers buying. We sit down, lay it all out, and go line by line. No one’s got time for bureaucracy. You want to cut errors? Start by asking ‘What’s in your bag?’ not ‘What’s in your chart?’ And stop assuming your EHR is talking to the next hospital - it’s not. Not even close.

Also, teach-back? That’s just common sense. If your grandma can’t say back in her own words why she’s taking metformin, you haven’t done your job. I’ve seen patients take insulin at bedtime because they thought ‘fasting’ meant ‘no food after midnight’ - not ‘before meals.’ They’re not dumb. The system just talks to them like they are.

And don’t get me started on nurses doing med reviews. Nurses are angels, yes. But they’re also juggling 12 patients, IV drips, and crying families. Pharmacists? We live in drug interactions. We dream in half-lives. If your hospital doesn’t have one at discharge, demand it. Or better yet - bring your own. I’ve had families hire private pharmacists just to walk them out the door. Worth every rupee.

precious amzy

December 11 2025One cannot help but observe the profound epistemological failure inherent in the current paradigm of pharmaceutical transition management. The very notion of ‘reconciliation’ presupposes a discrete, ontologically stable set of pharmacological entities - an assumption rendered untenable by the postmodern fragmentation of the self under late capitalism. Who, precisely, is the ‘patient’ when their medication regimen is mediated through institutional bureaucracy, technological interfaces, and the alienated labor of clinical personnel? The brown bag, far from being a tool of empowerment, becomes a fetishized relic of pre-digital authenticity - a performative gesture masking the systemic collapse of continuity of care. One must ask: Is the ‘teach-back’ method not merely a disciplinary technique, coercing the vulnerable into performative compliance with a medical episteme they neither control nor comprehend?

Courtney Black

December 13 2025It’s funny how everyone talks about pharmacists like they’re some kind of superhero. They’re not. They’re just another cog. The real problem? No one’s holding anyone accountable. Hospitals get paid for discharging you, not for making sure you don’t die the next week. And Medicare? They reimburse for TCM services, but only if the paperwork is perfect. So guess what? Hospitals do the bare minimum. They print a list. They check a box. They don’t sit with you. They don’t ask you to repeat it. They don’t even look at your brown bag. The system doesn’t care. It never has.

And tech? Apps don’t help if you’re 80 and your hands shake. A printed sheet taped to the fridge with a kid checking in every morning? That’s real care. Not algorithms. Not notifications. Just someone who cares enough to call.

Richard Eite

December 14 2025This whole article is just liberal nonsense. You want to fix medication errors? Stop letting old people live alone. Stop letting them take 12 pills. Stop letting them get discharged without family. America’s broken because we don’t respect elders - we just ship them out the door with a printout and hope. If you can’t manage your meds, maybe you shouldn’t be living alone. Simple. No apps. No pharmacists. Just responsibility. And stop blaming hospitals - blame the kids who don’t visit.

Gilbert Lacasandile

December 16 2025I really appreciate how thorough this is. I work in a small clinic in rural Ohio, and we’ve been trying to implement this stuff for years. We don’t have a full-time pharmacist, but we’ve trained our RNs to do a basic med reconciliation with a printed checklist and a phone call to the pharmacy. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than nothing. One thing we learned - even just asking patients to show us their pill organizer makes a huge difference. A lot of them are taking stuff they stopped months ago because they forgot to throw it out. Small steps, but they add up.

Also, I’ve seen firsthand how a simple 10-minute phone call from the pharmacy two days after discharge can catch a double-dose error. It’s not glamorous, but it saves lives.

Lola Bchoudi

December 17 2025Let’s talk about the clinical operational framework here. Medication reconciliation is not a discrete intervention - it’s a systems-level process that requires interprofessional alignment, documentation interoperability, and longitudinal care coordination. The 67% reduction cited in JAMA is statistically significant, but the real value lies in the reduction of polypharmacy-induced adverse events - particularly in geriatric populations with multimorbidity. The teach-back method isn’t just about adherence - it’s a cognitive reinforcement strategy that mitigates health literacy disparities. And yes, pharmacists are non-negotiable. Nurse-led models lack the pharmacokinetic expertise to detect Class I drug interactions - like combining NSAIDs with ACE inhibitors in CKD patients. If your discharge protocol doesn’t include a clinical pharmacist, you’re not providing safe care - you’re providing liability.

Also - brown bag reviews are the gold standard. Period. No digital solution replaces physical inspection of expired antihypertensives and leftover antibiotics from 2019.

Morgan Tait

December 17 2025You know what they don’t tell you? The hospitals are in cahoots with Big Pharma. They push new prescriptions because they get kickbacks - I’ve seen the spreadsheets. The ‘brown bag’? That’s just theater to make you feel safe. Meanwhile, your old meds are quietly deleted from the system so the pharmacy fills the new ones - even if you’re still taking the old ones. And the ‘teach-back’? That’s a trap. They ask you to repeat it so they can say ‘You didn’t understand’ if you end up back in the ER. They don’t want you to get better - they want you to keep coming back. I’ve been through this. My uncle died because they switched his blood thinner and didn’t tell him the old one was still active. The system is rigged. And no one’s gonna fix it unless we burn it down.

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

December 19 2025It is, of course, lamentable that the dissemination of best practices in pharmaceutical transition care remains inconsistent across institutional settings. The empirical evidence supporting pharmacist-led reconciliation is, indeed, compelling. However, one must question the generalizability of these findings within resource-constrained environments, particularly in light of workforce shortages and the absence of standardized protocols. Furthermore, the reliance upon the ‘brown bag’ methodology assumes a level of patient agency and cognitive capacity which may not be universally present. The utility of the teach-back technique, while theoretically sound, is contingent upon the communicative competence of both provider and patient - a variable which remains insufficiently accounted for in current literature.

Chris Marel

December 19 2025This is the kind of post that makes me feel less alone. My mom got out of the hospital last year and they gave her a list with 11 pills. She didn’t know what half of them were for. I had to drive 3 hours to help her sort through everything. I didn’t even know where to start. But the one thing that saved us? We called her pharmacy and asked them to print out her full history from the last year. That’s when we found the old blood thinner they forgot to cancel. We didn’t need a fancy app. We just needed someone to listen. Thank you for saying this out loud.