What Deep Brain Stimulation Actually Does for Parkinson’s

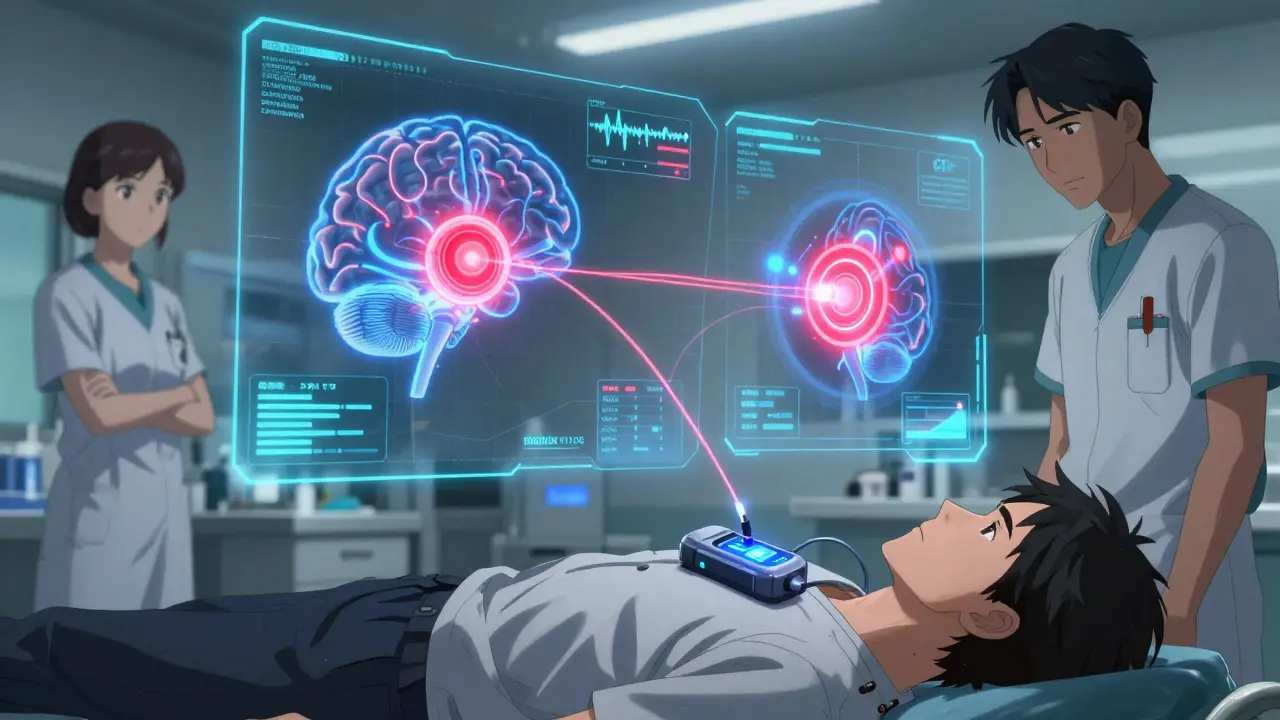

Deep Brain Stimulation, or DBS, isn’t a cure for Parkinson’s. It doesn’t stop the disease from progressing. But for the right person, it can turn a life of constant shaking, stiffness, and unpredictable freezes into one with more control, more independence, and fewer medication side effects. Think of it like a pacemaker for your brain - tiny electrodes deliver carefully tuned electrical pulses to specific areas that are firing out of sync. The result? Motor symptoms like tremors, rigidity, and slowness drop significantly. Many patients report cutting their daily OFF time - when meds aren’t working - from six hours to under an hour. Dyskinesias, those involuntary writhing movements caused by long-term levodopa use, often shrink by 80%. And because symptoms improve, people can reduce their daily levodopa dose by 30 to 50%.

The most common targets for these electrodes are the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the globus pallidus interna (GPi). STN stimulation tends to let patients cut back more on meds, which is great if side effects like nausea or hallucinations are a problem. But it can sometimes make thinking or speaking harder. GPi stimulation doesn’t reduce meds as much, but it’s better at smoothing out dyskinesias and has fewer cognitive risks. The choice isn’t one-size-fits-all - it depends on your biggest symptoms, your age, your brain health, and what matters most to you.

Who Is a Good Candidate for DBS?

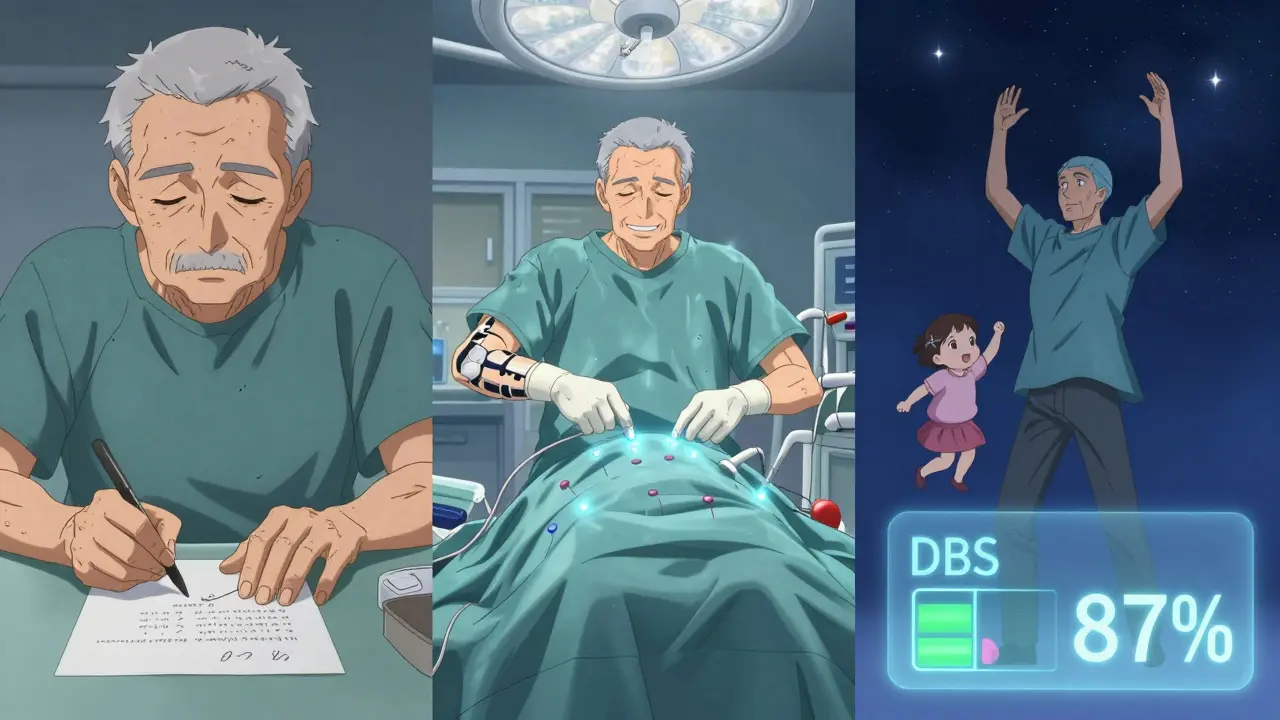

Not everyone with Parkinson’s qualifies. DBS only works well if your symptoms respond to levodopa. If you don’t feel better after taking your pill, DBS won’t help much either. The gold standard is a 30% or better improvement on the UPDRS-III motor exam when you’re on meds versus off. That’s not just feeling a little better - it’s being able to get out of a chair, walk across the room, or write your name without trembling.

You also need to have had Parkinson’s for at least five years. That’s because early on, meds still work well. DBS is meant for when those meds start failing - when you’re having ON-OFF swings, unpredictable freezing, or dyskinesias that make daily life unpredictable. If you’re still in the early stage where one pill a day keeps you moving, DBS isn’t the next step. Wait until the medication schedule becomes a full-time job.

Cognitive health matters too. If your memory, attention, or decision-making is already slipping - say, your MMSE score is below 24 or your MoCA is under 21 - DBS can make things worse. The brain needs to be able to handle the stimulation without adding confusion or depression. That’s why every candidate gets a full neuropsychological evaluation. It’s not just about motor skills. It’s about whether your brain can adapt to this change.

And here’s the big one: DBS doesn’t work for atypical parkinsonism. If you have progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, or corticobasal degeneration, you won’t benefit. These conditions don’t respond to levodopa, and they don’t respond to DBS either. Getting the diagnosis right is critical. Many people are misdiagnosed early on, and that leads to disappointment later.

The Evaluation Process: More Than Just a Doctor’s Visit

Getting approved for DBS isn’t a quick appointment. It’s a 3- to 6-month journey. First, you see a movement disorders neurologist who confirms your diagnosis and runs the levodopa challenge test. Then comes the neuropsychological battery - four to six hours of memory tests, attention tasks, and mood screenings. You’ll get a high-resolution 3T MRI to map your brain’s anatomy. This isn’t just a scan - it’s used to plan exactly where the electrodes go.

Then, the multidisciplinary team meets. Neurologist, neurosurgeon, neuropsychologist, and sometimes a speech therapist or social worker. They look at your entire picture: your symptoms, your meds, your family support, your expectations. One patient I spoke with thought DBS would fix his fatigue and sleep problems. It didn’t. That’s why the team has to make sure you understand what DBS can and can’t do. It helps movement. It doesn’t fix mood, memory, or balance issues - at least not yet.

Insurance approval adds another layer. Medicare covers DBS for Parkinson’s, but private insurers often want proof you’ve tried and failed on multiple medication regimens. That means keeping detailed logs of your ON and OFF times, your dyskinesias, and your daily functioning. Some centers have DBS coordinators who handle this paperwork. Others leave it to you. Don’t underestimate how long this takes - it’s not unusual to wait six months just to get the green light.

What the Surgery Actually Involves

The surgery happens in two parts, usually on separate days. First, the electrodes are placed. You’re awake during this part, with local anesthesia and light sedation. Why? Because the surgeons need you to move, speak, and respond so they can test the effects in real time. A frame is attached to your head. Tiny holes are drilled into your skull. Thin wires, thinner than a pencil lead, are guided into your target - STN or GPi - using MRI data and microelectrode recordings that pick up the brain’s electrical chatter. The whole process takes 3 to 6 hours.

A few days later, the pulse generator - the battery pack - is implanted under your skin, usually near your collarbone or abdomen. It’s about the size of a stopwatch. Wires run under your skin to connect it to the brain electrodes. You’re asleep for this part. Recovery is quick. Most people are home in a day or two. But the real work starts after surgery.

Programming and Adjustment: The Long Haul

DBS isn’t set and forget. The first programming session is usually four to six weeks after surgery. Then you’ll come back every few weeks for months. It takes 6 to 12 months to fine-tune the settings. Why? Because the brain changes. Stimulation needs change. Your meds change. Your symptoms evolve.

Modern devices like Medtronic’s Percept™ PC and Boston Scientific’s Vercise™ Genus™ can actually sense brain activity. They detect abnormal beta wave patterns (13-35 Hz) that signal stiffness or tremor. Some systems use that data to auto-adjust stimulation - a big leap forward. But even with smart tech, you still need regular visits. You’ll need to keep a symptom diary: when you feel stiff, when you shake, when your speech gets fuzzy. That’s the data your clinician uses to tweak voltage, frequency, and pulse width.

Some people get great results fast. Others struggle for months. One man on Reddit said it took him nine months to get his tremors under control. Another woman had to switch from STN to GPi after her speech got worse. Patience isn’t optional - it’s part of the treatment.

Real People, Real Outcomes

Most patients - 70 to 80% - see big improvements in movement. But the experience isn’t always smooth. One man, ‘ParkinDad2018’ on the Parkinson’s Foundation forum, said his OFF time dropped from six hours to one. His dyskinesias vanished. But he started forgetting words. He needed speech therapy. Another user on r/Parkinsons said his tremors were gone, but planning his meals now took three times longer. Executive function took a hit.

And expectations? That’s where things go sideways. A lot of people think DBS stops Parkinson’s. It doesn’t. It treats symptoms that respond to levodopa. If you’re struggling with balance, freezing, or swallowing - problems that don’t improve with meds - DBS won’t fix them. One patient wrote in a forum: ‘I thought it would give me back my life. It gave me back my walking. Not my balance. Not my voice. Not my energy.’ That’s the gap between hope and reality.

Hardware problems happen too. About 5 to 15% of people need a revision - a wire that moves, an infection, a battery that dies early. Non-rechargeable batteries last 3 to 5 years. Rechargeable ones last 9 to 15. But you still need to plug them in every week or two. That’s a lifestyle change.

What’s New and What’s Coming

The field is moving fast. Closed-loop DBS - systems that respond to your brain’s real-time signals - just got FDA approval in 2023. Early data shows 27% better symptom control than old-school DBS. That’s huge. Researchers are also testing DBS in patients with only 3 years of Parkinson’s. Could it work earlier? Maybe. And there’s new work on using genetic markers. People with LRRK2 mutations seem to respond better - that could one day help pick candidates more precisely.

But the biggest gap isn’t technology. It’s access. Only 1 to 5% of people who qualify for DBS actually get it. Many are never referred. Others wait until they’re too far gone. If you’re on a complex med schedule, struggling with dyskinesias, or feeling like Parkinson’s is stealing your independence - talk to your neurologist. Ask about a DBS evaluation. Don’t wait until you’re too tired to ask.

DBS vs. Other Options

There are alternatives. Focused ultrasound (Exablate Neuro) is non-invasive and FDA-approved for tremor-dominant Parkinson’s. But it only works on one side of the brain. And it’s not adjustable. Once done, it’s done. DBS can be tweaked. It can be turned off. It can be upgraded.

Lesioning procedures - like thalamotomy or pallidotomy - destroy a small part of the brain to stop symptoms. They’re effective, but irreversible. A mistake means permanent damage. DBS is reversible. If something goes wrong, you can turn it down or take it out.

And cost? In the U.S., DBS runs $50,000 to $100,000. Insurance usually covers it. But in other countries, access varies. In the UK, it’s available through the NHS, but wait times can be long. The bottom line: if you’re a good candidate, DBS is the most effective long-term tool we have for managing advanced Parkinson’s motor symptoms.

Final Thoughts: Is It Right for You?

DBS is powerful, but it’s not magic. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it only works if you’re the right person to use it. You need:

- A confirmed diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s

- Clear, consistent response to levodopa

- At least five years of symptoms

- No major cognitive or psychiatric issues

- Realistic expectations - it helps movement, not everything

- Willingness to commit to months of programming and follow-ups

If you check those boxes, DBS could give you back years of your life. If you don’t, it could make things harder. Talk to your team. Get the full evaluation. Don’t let fear or misinformation keep you from asking the question: Could DBS help me?

Can DBS stop Parkinson’s from getting worse?

No. DBS does not slow or stop the progression of Parkinson’s disease. It only treats the motor symptoms that respond to levodopa, such as tremors, stiffness, and dyskinesias. The underlying brain changes continue, and non-motor symptoms like balance problems, speech issues, and cognitive decline may still progress over time.

How long do DBS batteries last?

Battery life depends on the device. Non-rechargeable implants last 3 to 5 years and require a minor surgery to replace. Rechargeable systems, like Medtronic’s Percept™ PC or Boston Scientific’s Vercise™ Genus™, last 9 to 15 years but need weekly charging, usually for 30 to 60 minutes. Rechargeable batteries reduce the number of surgeries but add a daily routine.

Is DBS safe for older patients?

Age alone isn’t a barrier. Many patients over 70 do very well. What matters more is overall health, cognitive status, and mobility. If you’re otherwise healthy, have good brain function, and respond well to levodopa, age isn’t a reason to rule out DBS. But if you have heart disease, severe osteoporosis, or dementia, the risks of surgery may outweigh the benefits.

What are the biggest risks of DBS surgery?

The most serious risk is bleeding in the brain, which occurs in 1-3% of cases and can cause stroke-like symptoms. Infection happens in about 3-5% of cases and may require removal of hardware. Other risks include lead migration (the wire shifts), hardware malfunction, or temporary side effects like tingling, speech problems, or mood changes during stimulation. Most side effects can be fixed by adjusting settings.

Why do some people feel worse after DBS?

Some people experience new or worsened symptoms after surgery, especially if they had undiagnosed cognitive issues or unrealistic expectations. Stimulation can affect nearby brain areas, leading to speech problems, memory lapses, or mood changes. Sometimes, the improvement in movement makes people overdo it, leading to fatigue or falls. Others feel disappointed when DBS doesn’t fix non-motor symptoms like fatigue or depression. Proper screening and counseling help prevent this.

Can I have an MRI after getting DBS?

Yes, but only under strict conditions. Most modern DBS systems are MRI-conditional, meaning you can have a scan if the machine is set to specific safety settings and the device is turned off. You must inform the radiology team about your implant. Scans of the head are usually safe, but body scans carry higher risk. Always check with your DBS team before scheduling any MRI.

How soon after surgery will I feel better?

You won’t feel immediate relief. The brain needs time to adjust. Most people start seeing improvements 2 to 6 weeks after surgery, once the device is turned on and programmed. Full benefits often take 6 to 12 months as settings are fine-tuned and medications are adjusted. Patience is key - this isn’t a quick fix.

Will I still need to take Parkinson’s meds after DBS?

Yes, but usually less. Most patients reduce their levodopa dose by 30-50%, which helps cut down on side effects like nausea, hallucinations, and dyskinesias. You won’t stop meds entirely because DBS doesn’t help all symptoms. Some people still need small doses to manage symptoms DBS doesn’t fully control, like freezing or balance issues.

Alisa Silvia Bila

December 19 2025I had DBS last year. Tremors gone. Still need meds, but way less. Got my mornings back.

Best decision I ever made.

Marsha Jentzsch

December 19 2025Ugh, I hate how everyone acts like DBS is some miracle cure!! I know a guy who got it and now he can't even talk right!! He forgets his own kids' names!! They didn't warn him!! It's all just corporate hype!!

Janelle Moore

December 20 2025They're hiding something. DBS is a mind control experiment. The electrodes pick up your thoughts. That's why they make you stay awake during surgery. They're mapping your brain for the government. You think they care about your tremors? They want your memories.

Henry Marcus

December 21 2025DBS? More like Dumb Stimulation. They drill holes in your skull and zap your brain with some corporate gadget that costs more than my car. And don't even get me started on the rechargeable batteries-like, now I gotta be a human phone charger? Next they'll make us wear a DBS fanny pack. #BigPharmaLies

Sajith Shams

December 21 2025You people are misinformed. The data shows STN stimulation has a 47% higher rate of cognitive decline compared to GPi. Why are you not discussing this? The article barely mentions it. You need to read the 2022 Lancet Neurology meta-analysis. I have it saved. I can send you the PDF.

Adrienne Dagg

December 23 2025I’m so glad I found this!! 🙌 My dad got DBS and now he’s dancing again 😭💖 I cried when he held my baby without shaking. It’s not perfect but it’s a miracle!! Don’t listen to the naysayers!! 🤍

Erica Vest

December 24 2025The article accurately describes the indications, targets, and limitations of DBS. It correctly emphasizes that candidacy requires a robust levodopa response, absence of significant cognitive impairment, and realistic expectations. The distinction between STN and GPi targets is clinically nuanced and well-represented. No major inaccuracies detected.

Chris Davidson

December 24 2025DBS works for some people. Not for everyone. If you think its magic you are wrong. You need to be evaluated properly. Many skip the testing. That is why some fail

Andrew Kelly

December 26 2025Let’s be real-this whole thing is a scam designed to keep people dependent on expensive hardware. The real cure for Parkinson’s is diet, fasting, and detoxing your liver. But Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that. They profit from your fear. DBS? It’s just a placebo with wires. And those ‘smart’ devices? They’re listening. Always listening.

Dev Sawner

December 27 2025It is imperative to underscore that the selection criteria for deep brain stimulation must adhere to the most rigorous neuroscientific and ethical standards. The prevalence of misdiagnosed atypical parkinsonism remains alarmingly high, and the procedural risks, particularly intracranial hemorrhage, are not sufficiently contextualized in public discourse. Furthermore, the economic disparity in access to such interventions constitutes a profound global health inequity.

Moses Odumbe

December 27 2025I got DBS and now I charge my battery every Sunday like it’s my phone 😅 But honestly? Worth it. My wife says I’m human again. 🤖➡️👨🦳

Meenakshi Jaiswal

December 29 2025If you're considering DBS, please don't rush. Talk to at least three specialists. Keep a symptom journal. Bring a family member to appointments. The programming phase is hard, but you're not alone. Many of us have been there. You've got this.

bhushan telavane

December 30 2025In India, we don’t have many centers for this. My uncle waited 2 years just to get a consultation. Then they said he didn’t qualify. It’s sad. People suffer for years because no one tells them this is an option. This post should be shared everywhere.

Mahammad Muradov

December 31 2025The fact that this article even mentions 'realistic expectations' is a sign of institutional failure. If patients are being told DBS won't fix fatigue or speech, then why are they being sold this as a life-changing solution? It’s psychological manipulation disguised as medical care.

Kelly Mulder

January 2 2026I’m not impressed. This article reads like a Medtronic white paper. The tone is so sanitized. They never mention how many patients end up depressed after surgery because their identity was tied to their struggle. And the battery thing? Please. It’s not a device. It’s a prison you carry around. I’d rather shake than be a cyborg.

Alisa Silvia Bila

January 4 2026I read all these comments and I just want to say: I’m still here. Still walking. Still cooking. Still laughing. DBS didn’t fix everything. But it gave me back enough to matter. That’s enough.