When you write a prescription, you’re not just choosing a drug-you’re choosing a system. Generic prescribing means writing the International Non-proprietary Name (INN) of a medication, not the brand name. It’s not about cutting corners. It’s about clarity, cost, and consistency. In the UK, the NHS has been pushing this for decades, and for good reason: 89.7% of all prescription items in England are now issued generically. That’s not a trend. That’s standard practice. And if you’re not doing it, you’re missing the point.

Why Generic Prescribing Is the Default

Generic drugs aren’t cheap knockoffs. They’re exact copies of brand-name drugs, down to the active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. The FDA, EMA, and MHRA all require generics to pass strict bioequivalence tests-meaning they must deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream within a narrow range (80-125%) of the original. That’s not guesswork. That’s science.The savings are staggering. Atorvastatin, the generic version of Lipitor, costs £2.50 a month. The brand? £30. Omeprazole? £1.80 generic versus £15 for Losec. These aren’t hypotheticals. These are real numbers from NHS prescribing data. Across the UK, generic prescribing saves an estimated £1.3 billion every year. That’s money that can go toward more nurses, more mental health services, more cancer screenings. It’s not just about saving the NHS-it’s about making care sustainable.

There’s another benefit most people overlook: fewer medication errors. With one generic name per drug, you avoid the confusion of 15 different brand names for the same thing. A patient might get furosemide from one pharmacy, Lasix from another, and Frusemide from a third. That’s not just messy-it’s dangerous. Generic prescribing cuts that risk by half, according to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices.

When You Should Still Prescribe by Brand

This isn’t a blanket rule. There are exceptions. And they matter.The British National Formulary (BNF) lays out three clear categories where brand-name prescribing is still clinically necessary:

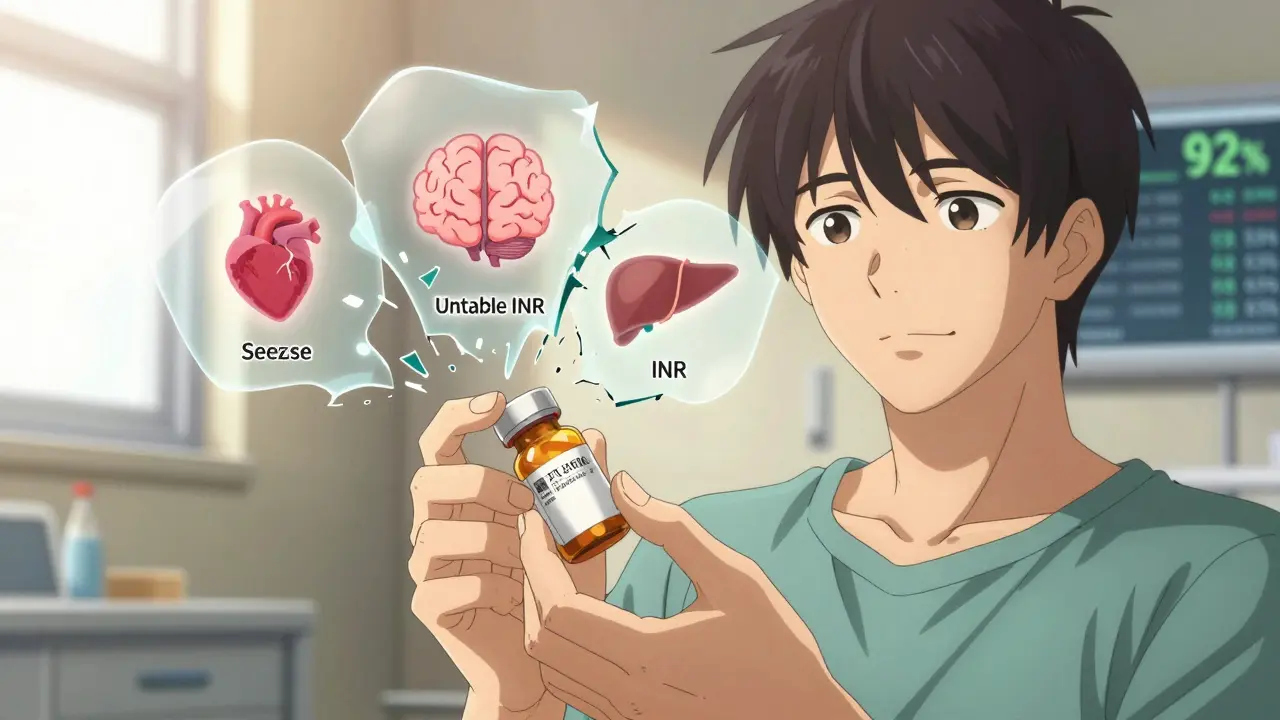

- Narrow therapeutic index drugs-where small changes in blood levels can cause harm. Think warfarin, digoxin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, and carbamazepine. For these, even minor differences in absorption between generic manufacturers can trigger INR spikes, seizures, or thyroid instability.

- Modified-release formulations-like theophylline or certain opioids. The way the drug is released over time can vary between brands. A patient stable on a 12-hour extended-release version might get a generic that releases too fast or too slow. Pharmacists report this is one of the most common sources of patient complaints.

- Biological medicines-insulin, TNF inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies. These are complex molecules made from living cells. Even small changes in manufacturing can trigger immune responses. That’s why the MHRA mandates brand-name prescribing for all biologics and biosimilars. No switching. No substitution. One product, one patient, one outcome.

That’s about 2% of all prescriptions. The rest? Generic is not just safe-it’s better.

What the Evidence Says About Patient Outcomes

Some clinicians worry patients won’t respond the same to generics. The data says otherwise.A 2017 JAMA study tracked over 100,000 patients on chronic medications. Those switched to generics had 15% fewer hospitalizations. Why? Lower out-of-pocket costs meant they actually took their pills. Generic prescribing improves adherence by 8-12%, according to the American College of Physicians. That’s not a minor bump. That’s life-changing.

There are exceptions, yes. A 2018 meta-analysis in Epilepsia found a 1.5-2.3% increase in seizure recurrence when patients were switched between generic versions of antiepileptic drugs-especially if they were switched multiple times. That’s why the American Epilepsy Society advises: if a patient is stable on a specific brand, don’t switch. But if they’re starting treatment? Start with the generic. Same for thyroid patients: levothyroxine is the most common cause of patient-reported “generic failure,” but studies show most of that is the nocebo effect-patients believe generics are inferior, so they feel worse. When doctors explain the science, patient acceptance jumps from 67% to 89%.

How to Implement This in Practice

You don’t need a revolution. You need a system.NHS England’s Generic Prescribing Toolkit gives you a four-step plan:

- Audit your prescribing-use the Prescribing Analytics Dashboard. See where you’re still using brand names. Is it habit? Fear? Ignorance?

- Learn the exceptions-keep the BNF’s three categories handy. Print them. Stick them on your desk. Memorize the top 10 drugs that need brand names.

- Set your e-prescribing system to default to generic-most systems let you do this. Turn off the brand-name auto-fill. Make generic the starting point.

- Monitor and adjust-track your rates monthly. Aim for 92%+. The rest? Document why you chose brand.

It takes 2-3 months for new prescribers to get comfortable. But once you do, it becomes second nature. You’ll stop thinking about it. And your patients will thank you.

Talking to Patients About Generics

The biggest barrier isn’t science. It’s perception.Patients hear “generic” and think “cheap.” They think “inferior.” You have to change that story.

Use this script: “This generic version has the exact same active ingredient as the brand you’ve been taking. It’s been tested to work the same way. The only difference is the price-it’ll save you about £12 a month, with no change in how well it works.”

Don’t say “It’s the same.” Say “It’s identical.” Don’t say “It’s cheaper.” Say “It’s more affordable.” Language matters. And if they’re still hesitant? Offer to keep them on the brand for now. But make it clear: it’s a choice, not a necessity.

The Bigger Picture

The global generic drug market is worth over $438 billion. In the US, generics make up 90% of prescriptions but only 17% of spending. In the NHS, generics are 89.7% of prescriptions but only 26% of drug costs. That’s the power of this approach.And it’s only getting stronger. By 2025, 75% of small-molecule drugs will have generic alternatives. Biologics? Slower, but biosimilars are growing fast. The future isn’t about choosing between brand and generic. It’s about choosing the right one-every time.

Generic prescribing isn’t a cost-cutting trick. It’s clinical wisdom. It’s evidence-based care. It’s what responsible prescribing looks like in 2026.

Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs must meet the same strict standards as brand-name drugs for active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and bioequivalence. Regulatory bodies like the FDA, EMA, and MHRA require generics to deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream within a scientifically accepted range (80-125%) of the original. Over 95% of generic drugs perform identically in real-world use. Any differences in effectiveness are typically due to patient perception, not pharmacology.

When should I avoid prescribing generics?

Avoid generic substitution for three types of drugs: (1) Narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin, digoxin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, and carbamazepine, where small changes in blood levels can cause harm; (2) Modified-release formulations such as theophylline or certain opioids, where release kinetics vary between manufacturers; and (3) All biological medicines, including insulin, TNF inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies, due to immunogenicity risks. These exceptions are clearly listed in the British National Formulary (BNF) and MHRA guidance.

Why do some patients say generics don’t work for them?

In most cases, it’s the nocebo effect-patients believe generics are inferior, so they experience side effects or reduced effectiveness simply because of that expectation. Studies show that when clinicians explain the science behind generics, patient acceptance increases from 67% to 89%. For a small subset of patients on antiepileptics or thyroid meds, switching between generic manufacturers can cause instability, but this is rare and usually avoidable with consistent dispensing.

Does prescribing generics increase the risk of medication errors?

No-the opposite. Brand-name drugs often have dozens of different names across markets and manufacturers (e.g., furosemide sold as Lasix, Frusemide, Furosemide). This creates confusion for patients and prescribers. Generic prescribing uses one standardized name per active ingredient, reducing naming errors by up to 50%, according to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices.

How do I know if a generic is approved in the UK?

All generic medicines in the UK must be licensed by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). You can verify this through the British National Formulary (BNF), which lists approved generics and flags any exceptions. Electronic prescribing systems also auto-populate only licensed generic options. If you’re unsure, check the MHRA’s publicly available database of licensed medicines or consult your local pharmacy team.

Can pharmacists substitute a brand for a generic without my permission?

In the UK, pharmacists can dispense a generic version if you prescribe by INN (generic name). But if you prescribe by brand name, they must dispense that brand unless you’ve written “DAW” (Dispense As Written) or “Do Not Substitute.” For narrow therapeutic index drugs and biologics, substitution is legally restricted. Always check your local pharmacy’s policy, but your prescription determines what they can legally give.

Trevor Whipple

January 14 2026generic? more like generic trash. i’ve seen patients go from stable to crashing after switching from Lipitor to some no-name pill. sure, the FDA says it’s ‘bioequivalent’-but bioequivalent doesn’t mean identical. my aunt had a stroke after they switched her to generic warfarin. they didn’t even tell her. that’s not science, that’s negligence.

Lethabo Phalafala

January 16 2026Y’ALL. I just had a 78-year-old man cry in my clinic because he couldn’t afford his brand-name insulin anymore. He said he’d been skipping doses. When I switched him to the biosimilar? He started sleeping again. He started walking his grandkids to school. This isn’t about money-it’s about dignity. If you’re still prescribing brand for everything, you’re not being clinical-you’re being cruel.

Lance Nickie

January 18 2026generic = bad. end of story. they’re made in china. need i say more?

Milla Masliy

January 19 2026I love how this post breaks it down so clearly. I’ve been using generics for years in my practice, and the biggest shift wasn’t clinical-it was cultural. I started saying ‘identical’ instead of ‘same,’ and ‘affordable’ instead of ‘cheap.’ Patients started nodding. One even thanked me for ‘not treating them like idiots.’ It’s wild how language changes outcomes.

Damario Brown

January 21 2026you think you’re saving money? think again. patients on generics miss more work. they report more side effects. the ‘nocebo effect’ is a myth-people aren’t imagining it. their bodies are reacting to inferior fillers, inconsistent binders, bad manufacturing. i’ve seen 12 different generic versions of omeprazole cause different GI symptoms. the NHS doesn’t care. they just want to cut costs. but patients aren’t data points. they’re humans with real guts, real livers, real lives.

sam abas

January 22 2026look, i get the savings. i do. but let’s be real-this whole generic push is just bureaucratic laziness dressed up as ‘evidence-based.’ you want to save money? fine. but don’t pretend it’s about patient care. the real issue is that prescribers don’t wanna think. they just click ‘generic’ and move on. what about the patient who’s been stable on a specific brand for 10 years? you just swap them out like a lightbulb. and then you wonder why they’re back in the ER. this isn’t medicine. it’s assembly-line healthcare. and the BNF exceptions? yeah, right. who’s gonna memorize those 10 drugs? no one. so they just default to generic anyway. and then we wonder why adherence drops. it’s not the drugs. it’s the system. and the system is broken.

John Pope

January 23 2026here’s the truth no one wants to admit: we’re not prescribing generics because they’re better. we’re prescribing them because we’ve given up on healing. we’ve outsourced care to algorithms and cost-per-pill metrics. we’ve turned physicians into pharmacy clerks. the real tragedy isn’t that generics exist-it’s that we’ve stopped asking: ‘what does this patient actually need?’ not the cheapest thing. not the most profitable thing. not the most convenient thing. the *right* thing. and if that’s a brand-name drug? we should have the courage to write it. but we don’t. because courage costs more than a few pounds.

Clay .Haeber

January 25 2026oh wow. a whole essay on how to be a good little NHS drone. congratulations. you’ve mastered the art of being a cost-saving automaton. next up: mandatory generic socks. ‘they’re made of the same cotton, just cheaper!’ you’re not a doctor-you’re a spreadsheet with a stethoscope. and don’t get me started on ‘identical.’ if it’s identical, why does the pill look different? why does the name change? why does the patient feel different? because it’s not identical. it’s a knockoff. and you’re proud of it? pathetic.

Priyanka Kumari

January 27 2026This is exactly what we need in global health-clear, compassionate, evidence-based guidance. In India, we face the opposite problem: patients can’t even access generics because of supply chain gaps. But when they do? The difference is life-changing. I teach my students: ‘Don’t prescribe the brand because you’re scared. Prescribe the right drug because you’re informed.’ And if a patient hesitates? Sit with them. Explain. Listen. That’s the real medicine. Not the algorithm. Not the savings report. The human moment.

Avneet Singh

January 29 2026the 89.7% stat is misleading. it doesn’t account for the hidden costs: increased pharmacy workload, patient non-adherence due to pill shape/size changes, and the fact that many generics are manufactured in facilities with substandard QA. the MHRA’s ‘approved’ label is a legal checkbox, not a guarantee of clinical equivalence. and let’s not pretend the NHS isn’t using this as an excuse to underfund drug research. this isn’t innovation. it’s austerity dressed in white coats.

Adam Vella

January 30 2026It is axiomatic that the principle of bioequivalence, as codified by regulatory agencies, constitutes a scientifically robust foundation for the substitution of branded pharmaceuticals with their generic counterparts. The assertion that patient-reported differences are attributable to the nocebo effect is empirically supported by randomized controlled trials, including the 2017 JAMA cohort study and the 2018 Epilepsia meta-analysis. Furthermore, the economic impact, quantified at £1.3 billion annually in the NHS, represents a material reallocation of resources toward systemic healthcare infrastructure. It is therefore not merely prudent, but ethically imperative, to standardize prescribing practices in accordance with evidence-based guidelines. To deviate without clinical justification constitutes a failure of professional duty.