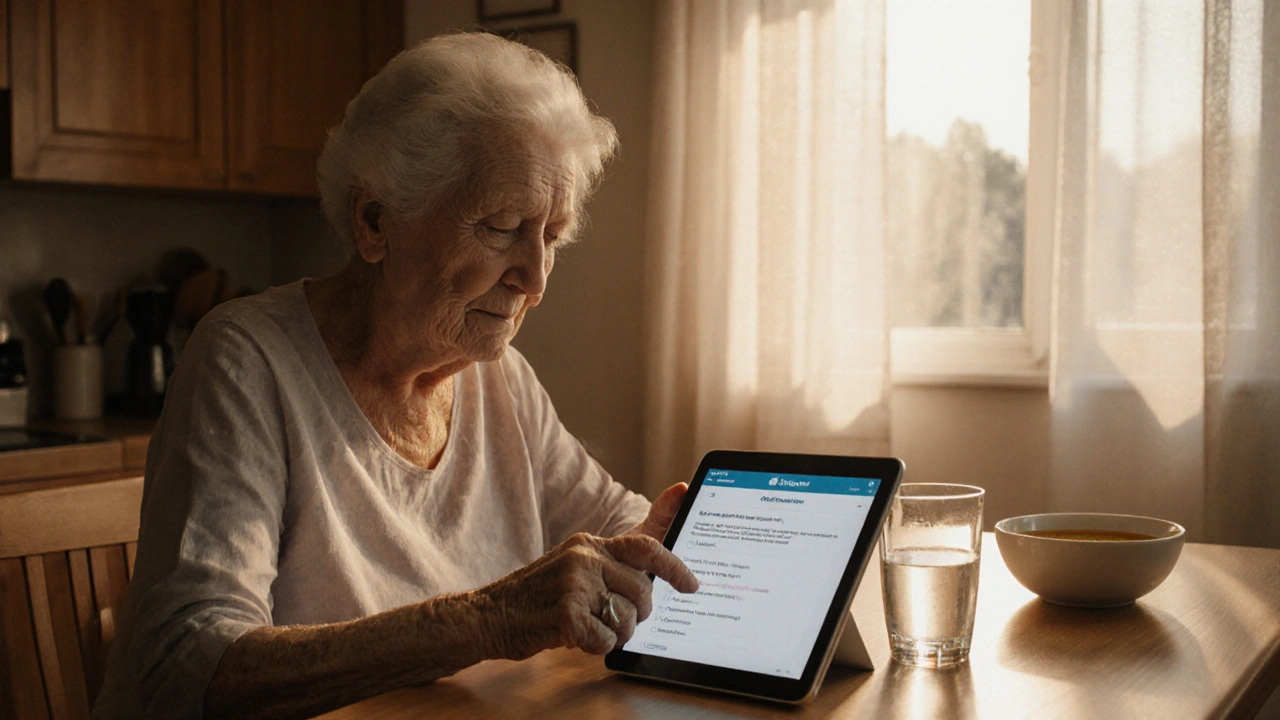

Hyponatremia Risk Assessment for Seniors

Enter your details and click "Assess Risk Level" to get personalized insights on hyponatremia risk and prevention tips.

Hyponatremia is a condition where the blood’s Sodium concentration falls below 135mmol/L. In older adults, even a modest drop can trigger confusion, falls, or life‑threatening brain swelling. This guide explains why seniors are especially vulnerable, how to spot the problem early, and what practical steps you can take to keep sodium levels steady.

Quick Takeaways

- Low serum sodium is common in people over 65, often linked to medications or chronic illnesses.

- Key warning signs include sudden dizziness, nausea, headache, or altered mental status.

- Preventive measures focus on balanced fluid intake, medication review, and regular lab checks.

- Mild cases can be treated with oral salt tablets; severe episodes need Intravenous Saline under medical supervision.

- Prompt treatment reduces hospital stays and cuts the risk of long‑term cognitive decline.

Why Hyponatremia Hits Older Adults Hard

Age‑related changes in kidney function and hormone regulation make the elderly prone to fluid‑electrolyte imbalances. The Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH) tends to stay elevated, causing the kidneys to retain water even when serum sodium is already low. Combine that with reduced thirst perception and you have a perfect storm for dilutional hyponatremia.

Studies from the UK National Health Service show that up to 20% of hospitalised patients over 70 present with serum sodium below 130mmol/L. The condition isn’t just a lab oddity; it correlates with a 30% increase in in‑hospital falls and a 15% rise in 30‑day mortality.

Common Triggers and Risk Factors

Several everyday factors can push sodium levels down:

- Medications: Thiazide diuretics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are frequent culprits.

- Chronic diseases: Congestive heart failure, liver cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease all impair fluid regulation.

- Syndrome of Inappropriate ADH Secretion (SIADH): Certain cancers and pulmonary disorders trigger excess ADH release, leading to water retention.

- Excessive water intake: Over‑hydration, especially during hot weather or after intense exercise, dilutes sodium.

- Dehydration: Paradoxically, low fluid intake can also cause hyponatremia because the body conserves water and concentrates ADH.

When multiple risk factors overlap - for example, an elderly patient on thiazides who also has heart failure - the chance of a sudden sodium drop spikes dramatically.

Spotting the Signs Early

Older adults may not describe “low sodium” directly. Instead, look for subtle clues:

- New‑onset confusion or trouble concentrating

- Unexplained falls or gait instability

- Morning headaches that improve with coffee

- Nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite

- Muscle cramps or generalized weakness

If any of these appear after a medication change or a period of increased fluid consumption, a quick blood test is warranted.

Prevention Strategies You Can Use

Preventing hyponatremia is often about small, consistent habits:

- Review medications regularly: Ask the GP or pharmacist to assess the need for thiazides, SSRIs, or any drug known to affect sodium.

- Monitor fluid intake: Aim for 1.5-2L of water per day, but adjust based on heart or kidney status. Encourage sipping rather than large gulps.

- Balance meals with electrolytes: Include soups, broth, or a pinch of sea salt in meals, especially for those on low‑sodium diets.

- Schedule periodic labs: For high‑risk patients, check serum sodium every 3-6months.

- Educate caregivers: Provide a simple checklist of symptoms and a reminder to report sudden changes.

These steps cut the likelihood of a severe drop by roughly half, according to a 2023 cohort study in the Journal of Geriatric Medicine.

Management Options in Acute and Chronic Cases

The treatment goal is to raise sodium safely without causing rapid shifts that could damage brain cells. Here’s how clinicians typically approach it:

| Aspect | Mild (130-135mmol/L) | Severe (<125mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Common Symptoms | Fatigue, mild nausea | Seizures, profound confusion |

| First‑line Treatment | Oral salt tablets, fluid restriction (≈800mL/day) | Controlled Intravenous Saline infusion (3% NaCl) |

| Target Sodium Rise | ≤4mmol/L per 24h | 4-6mmol/L per 24h, never >8mmol/L |

| Hospitalization Risk | Low (outpatient follow‑up) | High (monitor in ICU or step‑down unit) |

For chronic cases, slowly increasing dietary sodium over weeks is often enough. Some clinicians add a low‑dose demeclocycline to blunt ADH, but this is reserved for refractory SIADH.

Never attempt to correct severe hyponatremia with plain water or milk; rapid dilution can worsen cerebral edema.

When to Call a Doctor

If an elderly person shows any of the following, seek medical advice immediately:

- Sudden confusion or inability to recognize familiar faces

- Seizures or loss of consciousness

- Persistent vomiting that prevents keeping fluids down

- Noticeable swelling in the ankles combined with rapid weight gain

Early intervention often means the difference between a brief observation stay and a prolonged ICU admission.

Next Steps & Troubleshooting

After a hyponatremia episode, the focus shifts to preventing recurrence:

- Update the medication list - consider switching from a thiazide to a calcium‑sparing diuretic if blood pressure control permits.

- Set up a home‑visit nurse to track daily fluid intake and weight.

- Use a simple logbook: date, fluid volume, any symptoms, and medication changes.

- Re‑test serum sodium two weeks after discharge, then monthly for three months.

If sodium stays low despite these measures, ask the doctor about evaluating for hidden causes such as adrenal insufficiency or occult malignancy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can drinking too much water cause hyponatremia in seniors?

Yes. While staying hydrated is important, excessive water intake can dilute blood sodium, especially when the kidneys can’t excrete the excess fast enough. Aim for moderate, steady sipping rather than large volumes at once.

Are salt tablets safe for older adults?

Salt tablets can raise sodium quickly and are safe when used under medical guidance. Patients with hypertension or heart failure need a doctor‑approved dosage to avoid fluid overload.

How often should serum sodium be checked in high‑risk seniors?

For those on thiazides, SSRIs, or with chronic heart/kidney disease, a check every 3-6months is advisable. After any medication change, repeat the test within two weeks.

What is the role of hyponatremia in causing falls?

Low sodium can impair brain function, leading to dizziness and poor coordination. Studies link hyponatremia with a 30% rise in fall risk among residents of long‑term care facilities.

Is SIADH a common cause of hyponatremia in the elderly?

SIADH accounts for about 10% of hyponatremia cases in seniors, often linked to lung infections, certain cancers, or neurologic diseases. Treating the underlying condition usually resolves the sodium imbalance.

Prateek Kohli

October 2 2025Hyponatremia can sneak up on older adults when they’re drinking too much water or taking the wrong meds 😊. It's crucial to balance fluid intake and keep an eye on diuretics and antidepressants. Simple adjustments like monitoring daily liters and reviewing prescriptions with a doctor can make a big difference.

Noah Seidman

October 4 2025People need to understand that pushing seniors to limit fluids without medical guidance is a moral failure. The healthcare system often treats the elderly as numbers, not humans. We must demand evidence‑based protocols, not blanket recommendations.

Anastasia Petryankina

October 5 2025Oh great, another "interactive" tool that pretends to care while drowning us in jargon. As if senior citizens needed more digital headaches.

Gary Smith

October 7 2025THIS IS WHAT OUR NATIONS NEED!!! A CLEAR CALL TO LIMIT EXCESSIVE WATER INTAKE!!! NOTHING ELSE MATTERS!!!

Dominic Dale

October 9 2025The app that claims to calculate hyponatremia risk is just a front for a larger data harvest.

Every input you give about age and fluid intake is being logged by hidden servers.

They then cross reference with pharmaceutical databases to push you toward certain drugs.

The thiazide diuretics you see listed have been quietly phased out by health agencies that are in league with big pharma.

The same agencies also control the guidelines that say seniors should limit fluids to two liters a day.

This so‑called “prevention tip” is a way to keep you dependent on their patented water‑monitoring devices.

Those devices feed back data that triggers more alerts and more sales.

Meanwhile, the SSRIs you may be on are part of a neuro‑chemical manipulation program.

They alter your perception of thirst so you never question the fluid restrictions.

Chronic kidney disease is often misdiagnosed to keep patients on costly dialysis rigs.

The cirrhosis warnings are a distraction from the real issue: electrolytes are being weaponized in hospitals.

In many regions the low sodium alerts are calibrated to trigger unnecessary IV saline infusions that are funded by the saline manufacturers.

The whole risk‑assessment interface is a veneer for a deeper agenda to monitor and monetize every senior’s bodily functions.

If you look closely you’ll see that the color scheme of the site matches the branding of a major health data conglomerate.

That is no coincidence because the data you enter is fed into an AI that predicts who will need the next round of prescription drugs.

The only true prevention is to disconnect from these platforms and rely on community‑driven health practices.

christopher werner

October 10 2025I appreciate the thorough breakdown, thank you.

Matthew Holmes

October 12 2025Wow, the truth is out there and the hidden forces are pulling the strings.

They want you scared of water, scared of meds, scared of your own body.

Wake up and see the drama for what it is.

Patrick Price

October 13 2025i think the site is realy helpful but i had a problem with the form sorry for the typo.

the fluid intake field wont accept 2.5 and it keep saying error.

maybe they need to fix that soon.

Travis Evans

October 15 2025Hey crew, great to see everyone talking about this! Remember, staying hydrated is key, but don’t go overboard-aim for about 1.5‑2 L unless your doctor says otherwise.

Pull up those medication lists and double‑check with your pharmacist; thiazides and SSRIs can be a risky combo.

If you’ve got heart failure or kidney issues, keep those check‑ups regular and ask about sodium‑free options.

Bottom line: small, consistent habits beat big, risky swings every time.

Danielle Watson

October 16 2025Interesting points about fluid limits and medication interactions.

Just a heads‑up: the tool’s UI could use clearer labeling on the input fields.

Overall, it’s a useful start for seniors to stay aware.